Columbus Day is met with hostility and skepticism today, largely because Columbus himself was such a controversial character. Maybe he isn’t the best messenger for this day, but, at its roots, the day isn’t really about him. The story of how the day came to be celebrated in America is not one of colonialism, or European supremacy, or anything else it’s come to be labeled. Quite the opposite, actually. It’s about a group of struggling immigrants who celebrated one of their own that they knew their Western European neighbors could respect. It’s a story of immigrants trying to fit into American society while celebrating their own culture. In focusing on the vices of the holiday’s namesake, we shouldn’t ignore what the day has come to represent for millions of Italian-Americans. As this Huffington Post article correctly states, at its roots Columbus Day was about inclusion, not about Columbus.

There had already been some sporadic recognition in the United States of the anniversary of Columbus’s fateful voyage in 1492, but it had never quite become the phenomenon it was once the Italian-Americans got involved. For Italian-American immigrants at the turn of the last century, Christopher Columbus represented something almost unimaginable to them: an Italian whose accomplishments white Americans would respect.

Maybe the Italian-Americans could have picked someone less controversial. Hindsight is 20/20, and most of the facts and accusations about Columbus were either unknown or less known a hundred years ago. Now it’s probably too late to change the name to Galileo Day or Michelangelo Day or a day for any number of Italian-born saints, scientists or scholars. The Irish-Americans were wiser or luckier with their holiday choice, and once a year we have a day when everyone claims to be at least a little Irish. The Italians have had no such luck.

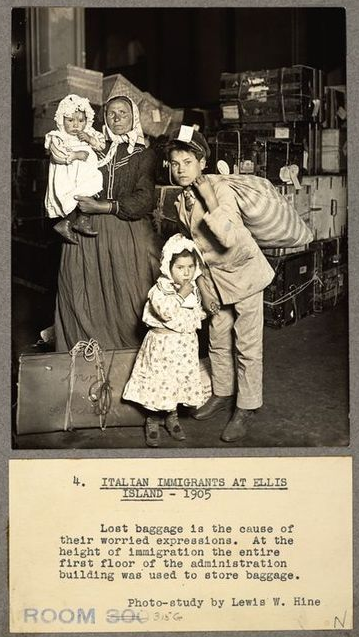

The meaning of both Columbus and Columbus Day has changed over time, as has the status of Italian-Americans. At the turn of the twentieth century the Italians were the new immigrant group: with a strange new religion (Catholicism) and strange customs, surging into America in a seemingly unending stream from their home country. For them, Columbus Day was a point of pride. For us today, it can be a reminder of how quickly times change, how past prejudices look absurd from the clarity of the future, and how perceptions and biases that seem cemented into society can melt away with time. To dismiss the rich history and culture that the holiday has represented for decades is to ignore the hard lessons that American society has been forced to learn.

As Yoni Appelbaum at The Atlantic so nicely put it “It’s worth remembering that the now-controversial holiday started as a way to empower immigrants and celebrate American diversity.”

In 1907, an Italian immigrant living in Colorado named Angelo Noce convinced the state’s only Hispanic state senator, Casimio Barela, to sponsor a bill proclaiming Columbus Day as an official holiday. Thanks to Angelo’s work, Colorado became the first state celebrate Columbus Day in 1909. Barela was an immigrant himself, having been born in what is now New Mexico while that territory was still part of Mexico.

According to Lakshmi Gandhi at NPR:

“Because Italian-Americans were struggling against religious and ethnic discrimination in the United States, many in the community saw celebrating the life and accomplishments of Christopher Columbus as a way for Italian Americans to be accepted by the mainstream. As historian Christopher J. Kauffman once wrote, ‘Italian Americans grounded legitimacy in a pluralistic society by focusing on the Genoese explorer as a central figure in their sense of peoplehood.'”

Later in the article, Gandhi discusses the fight to get the holiday recognized:

“Noce and fellow Italian-American Siro Mangini dreamed of honoring Christopher Columbus and worked with Colorado’s first Hispanic state Sen. Casimiro Barela, to sponsor a bill proposing a Columbus Day holiday. (Interestingly, Siro Mangini owned a tavern named after Columbus. As his daughter recalled, “He finally decided to call it Christopher Columbus Hall, thinking that he was [the] one Italian [that] Americans would not throw rocks at.”) Within five years of Colorado’s creating the holiday, 14 other states were also celebrating Columbus Day.”

That line in itself summarizes so much about the motives behind people who pushed for the holiday, “he was the one Italian that Americans wouldn’t throw rocks at.” This was a time in which, according to The Atlantic, a New York Times editorial called Sicilians “a pest without mitigation.”

Here’s a good timeline of how the holiday came to be, via the Smithsonian.

Obviously, Columbus isn’t without his faults. But so little of this holiday is actually about Columbus himself. In New York and New Jersey and other Italian enclaves, if there’s celebration of Columbus’s voyage it’s few and far between. Instead, it’s a day of Italian flags, of good food, of proudly declaring your Italian-American heritage and remembering the hardships that past generations struggled to overcome. That’s what’s at stake, and that’s why Italian-American groups, regardless of their political affiliation, take offense at the idea of having their holiday repealed.

If you like what you see here, follow Modern Cereal Box on Twitter. Feel free to tweet at @ModernCerealBox or email moderncerealbox@gmail.com. While you’re at it, be sure to check out the MCB Instagram account for some of my favorite travel photos and stories: https://www.instagram.com/moderncerealbox/